What you’re doing right now? Running your eyes over these little scribbles and digital scratches and conjuring meaning from them? Tapping into the brain of someone you’ve never met, from hundreds of miles away, to expand your knowledge and perspective? That’s pretty damn punk.

Reading has always been, and will always be, a revolutionary act.

That might reek of hyperbole to the average American living in 2025, who easily spends hours every day reading. Even if they haven’t cracked a book since high school, they’re constantly reading: billboards and Amazon product packages, fast food menus and road signs, social media posts and break-up texts and IKEA assembly instructions.

Yet, we take this ability for granted. Especially if you are a minority and/or a woman, your ability to read is nothing short of miraculous. We stand on the shoulders of giants, many of whom gave their lives so that we would have the chance to learn to read. We’ve been lulled, however, by apathetic teachers and poorly constructed educational curricula into believing that reading is boring and lame and a waste of time.

A formidable weapon has been placed in our hands, and we never use it.

Or maybe we do read. We read what we’re told. We read what they give us. We read what we’re allowed. I’ve written in a prior post about how five publishers (called the Big Five) control 80% of the publishing industry, which means that five corporations dictate 80% of what you’re allowed to read—not through legislation but through access. If we never get curious, never step off the safe prescribed path of big, box bookstores and the same ten recommendations that always seem to be circulating on BookTok, we stay squarely in that 80%, and we’re not a threat.

Maybe we read for status or the “book aesthetic.” There are literary stylists now who help fashion designers and celebrities pair books with runway ensembles and curate home libraries. Last year, Ashley Tisdale got backlash when she admitted to Architectural Digest that her home library was stocked with 400 random books, thoughtlessly bought, simply for the aesthetic of it all:

We’re seeing an undeniable return to books and personal libraries as status symbols without regard for their actual purpose: personal learning, growth, and the expansion of one’s mind. Instead of being read, discussed, and wrestled with, books are curated like designer handbags, displayed for clout rather than intellectual engagement. It’s a hollow performance, a ritual of ownership rather than understanding, where the presence of books is mistaken for the presence of thought.

This trend isn’t new, unfortunately. It’s as old as books themselves. But it’s still a gross abdication of tremendous and essential power. And in a modern era where the works of Orwell, Bradbury, and Huxley feel less like fiction and more like prophecy, this trend isn’t just shallow; it’s dangerous. A culture that prizes the illusion of intellect more than actual critical thinking is one that sleepwalks toward the very dystopias these books tried to warn us about.

My goal with this essay is to awaken you to your formidable power as a reader, to inspire and enlighten you to the potential you have to significantly affect change without even getting off your couch. They don’t want you to know about this. The Big Five and certain politicians and some religious leaders and a handful of tech billionaires…they all hope you never find out just how powerful you and your reading choices are.

Reading is still punk AF.

They Will Kill To Keep You Out

Literacy has been a stark delineator between classes, genders, and races for most of history. In the West, the Church historically used language barriers1, censorship, and control over education to limit access to the written word. Literate clergy and educated elites, both almost exclusively male, were the only ones privileged to read, write, and interpret written works. This allowed them to spread content that supported their authority, thoughts, and beliefs while burying theological, philosophical, or scientific content they considered to be heretical or dangerous2.

In the eighth century, Charlemagne issued decrees like the Admonitio Generalis that implemented widespread educational reform, kickstarting the Carolingian Renaissance and allowing girls to learn to read for the first time. Charlemagne aimed to create a more capable and unified empire, hoping that an educated lower class would be more efficient and that literate women would either become learned nuns or mothers who could better educate their male children.

Degrading. But still: women were finally able to read, and there’s no going back from that. The Church controlled most educational institutions at the time, including cathedral schools and early universities, which focused heavily on teaching religious content and tightly controlling access to broader knowledge. While the Church could do nothing about changing Charlemagne’s decrees, they could use other methods to gatekeep and exclude. Instead of Latin (which was often taught exclusively to boys), girls were taught to read and write in the common vernacular. This intentionally restricted women from reading the Vulgate (the Latin translation of the Bible) because men in positions of power feared women gaining the ability to read and interpret scripture on their own.

“A big worry was that [reading] was something they could do alone, without anyone to guide their thinking,” writes Joan Acocella in a piece for The New Yorker. But don’t take Acocella’s word for it, let the clergymen speak for themselves. In Malleus Maleficarum (or Witch Hammer)3 written in 1487 by clergymen, they take great care to unequivocally prove: “When a woman thinks alone, she thinks evil.”

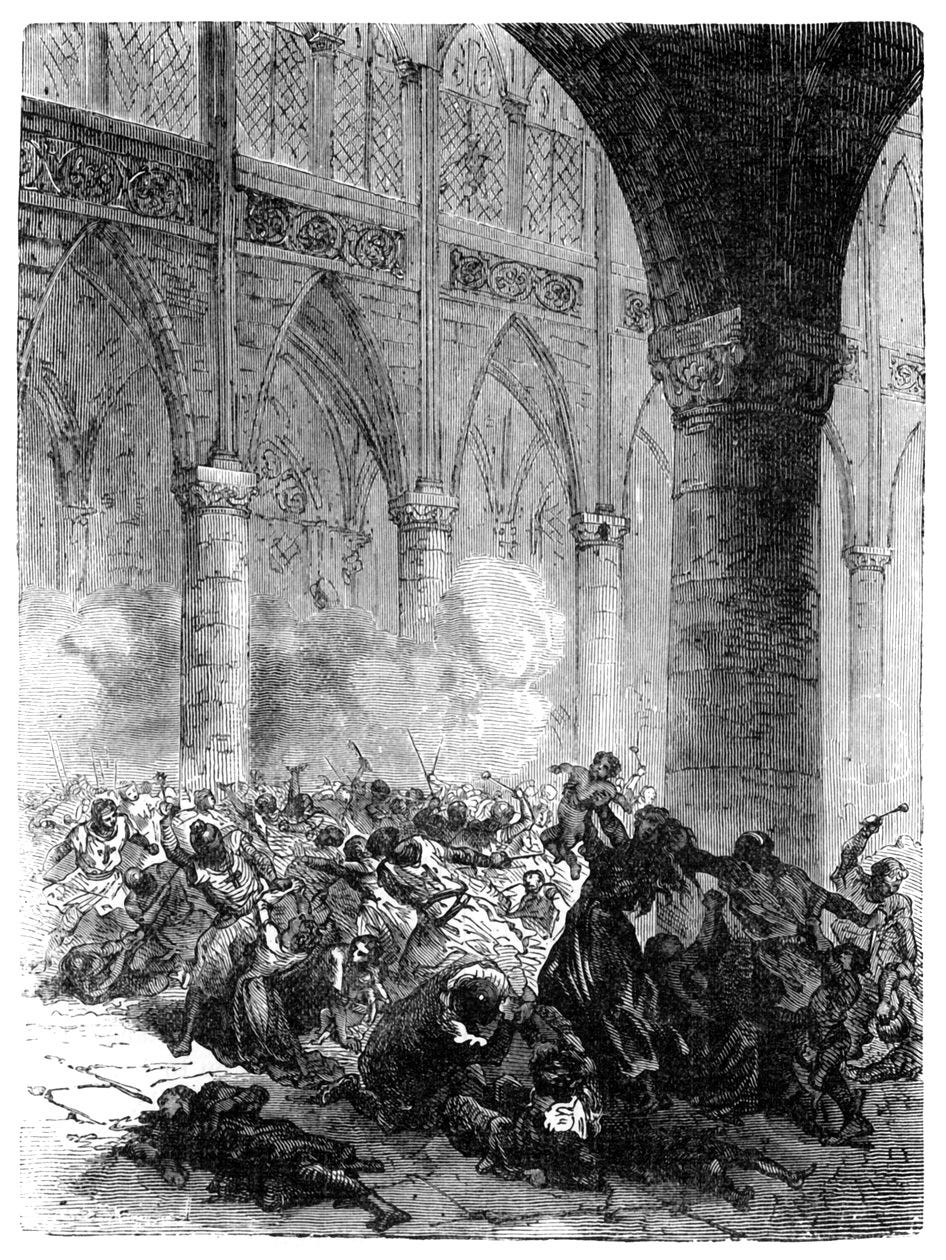

There were movements to translate the Vulgate into vernacular, like the one led by the Cathars. But the Church deemed them heretical, and in 1209, Pope Innocent III launched a brutal military campaign to exterminate them. Led by French nobles, crusaders massacred entire Cathar towns. When asked how to distinguish Cathars from Catholics, a Church official allegedly said,

"Kill them all, God will know His own."

As with all conflicts, the issues were layered and not exclusively about literacy. But literacy was undoubtedly at the forefront, and I tell you this so you know I am not exaggerating when I say that people in power have historically feared your ability to read, think, and wonder independently—even going so far as to kill to keep you out.

They Will Disparage You To Keep You Out

Having been taught to read in the common vernacular, girls naturally read books written in the common vernacular. With the introduction of Gutenberg’s press in the mid-15th century, all books (including vernacular literature) were becoming more accessible. Men in power found another problem with that:

“Vernacular literature was frequently scorned by men,” Acocella goes on, “because it tended to be sentimental and realistic: ballads and [verse stories] about love and friendship and animals and magic potions.” The scorn and ridicule thrown at modern-day female-dominated genres like romantasy are, apparently, not new.

Ultimately, men worried that these books were teaching women to “think independently,” says Acocella, and they were afraid that women “might cease displaying the attractions—sweetness, soft voices, compliance—that were the product of their dependence on male approval. Indeed, they might start talking back to men. They did.”

This started during the Enlightenment, and by the 16th and 17th centuries, publishers could produce small, inexpensive books that women could easily buy (and hide from their husbands and fathers).

By the 19th century, English citizens could borrow one book at a time through Mudie’s for a guinea a year. Think “the Netflix of the 19th century.” Free public libraries became more popular by the end of the century, but until then, Mudie’s was singular in getting books into the hands of readers (even while causing problems elsewhere for writers and readers).

By this time, protests by reading women against misogyny became more pointed, organized, and frequent. “As men feared, books caused women to imagine a different life for themselves...”

Between the pages, women engaged with ideas about God, spirituality, courage, independence, equality, feminine pleasure, camaraderie with other women, choice, autonomy, sexuality, motherhood, government, class, economics... They were discovering ideas that would have remained beyond their reach had they not been able to read. These are ideas that we still, to this day, meet most often on the page.

It became increasingly clear to the more enterprising powerholders that there was no way to put the cork back into the bottle: women were not going to stop reading. Their next best hope was to control what women could read, not through language as attempted by the Church, but through publishing.

Presbyterian minister James Fordyce published Sermons to Young Women in 1766 in order to exhort female readers to be modest, chaste, and deferential to men. “Remember,” he warns (or threatens?), “how tender a thing a woman’s reputation is, how hard to preserve, and when lost how impossible to recover.”

But tightfisted men faced another obstacle in publishing, one they feared greatly.

Historically, for men in power, the only thing scarier than a woman holding a book is a woman holding a pen.

They Will Discredit You To Keep You Out

“America is now wholly given over to a damned mob of scribbling women, and I should have no chance of success while the public taste is occupied with their trash—and should be ashamed of myself if I did succeed.”

Nathaniel Hawthorne4 wrote this to his publisher in the 1850s, obviously frustrated by the fact that he was being outsold by female writers, like:

Harriet Beecher Stowe, who wrote Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852): one of the most influential books of the 19th century and massive bestseller that helped shape American public opinion on slavery.

Susan Warner, who wrote The Wide, Wide World (1850): often considered America’s first bestseller, this novel was about a young girl’s struggles, faith, and perseverance.

Fanny Fern, one of the highest-paid newspaper columnists of the era, who wrote Ruth Hall (1854): a semi-autobiographical novel that critiqued gender roles, marriage, and the literary marketplace.

Harriet Jacobs, who wrote Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (1861): one of the first autobiographical narratives by a formerly enslaved woman, detailing her harrowing escape and survival.

That damned mob and their “trash.” And poor baby Nat, grinding away at serious literature, only to get absolutely bodied at the bookshop by these “scribbling women.”

Nat wasn’t alone in his feelings, and his statement merely scratched the surface of the historically prevalent attitude toward women who decided to write.

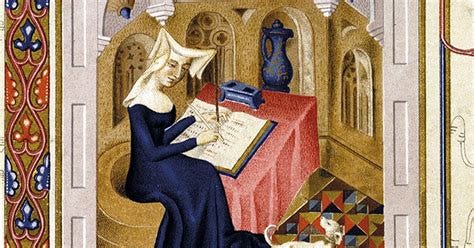

From the beginning, trailblazing female writers had to tread a fine line. They were sometimes praised if they presented their written works as a divine gift, as was the case with Abbess Hildegard of Bingen (1098–1179). Pope Eugenius III endorsed her mystical writings and encouraged her to continue writing. However, other male clerics questioned whether she should be allowed to write, teach, or interpret scripture. To make her words more acceptable in the male-dominated Church, she had to frame her knowledge as a divinely inspired gift rather than a product of her own intellectual effort.

Other writers who claimed too much intellectual authority risked backlash, silencing, or even charges of heresy. Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz (1648–1695), a Mexican nun and scholar whose writings challenged male theologians, was eventually pressured into silence by Church authorities.

Other women were simply erased. Trota of Salerno was a female physician who wrote medical texts in the 12th century, but her work was absorbed into male-authored texts. Her name was almost completely lost to time and historians by those who claimed that the writings were by male authors about women’s medicine, when in fact it was a woman’s writings about women’s medicine.

Still others like Christine de Pizan (1364–1430), the first known professional female writer in Europe, faced constant opposition. She had to defend women’s intelligence in The Book of the City of Ladies against male scholars who claimed women were naturally inferior.

Despite this, many persisted, leaving behind legacies that shaped theology, science, literature, and more.

As the Enlightenment dawned, more women endeavored to pick up a pen, and they continued to experience pushback:

Anne Bradstreet (1612–1672) couldn’t publish her poetical works as a Puritan woman, but her brother-in-law, John, could. He published her works without her involvement5 making her America’s first published poet.

Some men mocked the idea of a woman writing poetry, which prompted poet and minister Nathaniel Ward to write in her defense:

"Let Greeks be Greeks, and women what they are;

Men have precedency, and still excel,

It is but vain unjustly to wage war,

Men can do best, and women know it well."Or, to summarize, "Yeah, she's good—for a woman. We, mighty men of genius, aren’t threatened." Even their allies found ways to belittle early female writers.

Margaret Cavendish (1623–1673) was a philosopher, scientist, and one of the first women to write science fiction. She publicly debated male scholars (to their disgust) and wrote about atoms, nature, and gender roles at a time when women were not supposed to be involved in intellectual life.

Aphra Behn (1640–1689) was a spy turned playwright and the first woman in the Western world to make a living from writing. She was ridiculed for her plays being too sexual with Alexander Pope mocking her in poetry by calling her a writer of “lewd novels” (a degree of criticism male playwrights did not receive).

Eliza Haywood (1693–1756) wrote bold, sensual stories about women navigating love and power; she was called trashy and immoral.

Maria Stewart (1803–1879) was a Black writer, lecturer, and activist from Massachusetts, known for her eloquent speeches and writings on racial and gender equality. She faced hostility from both Black and white men who were uncomfortable with a woman speaking publicly about issues of race and gender.

Phillis Wheatley (1753–1784) was a poet, born in Senegal and enslaved in Boston. She became the first African American woman to publish a book of poetry and, as a Black woman, faced far more ridicule and resistence than her white female writer counterparts.

Jane Austen and Mary Astell and the Brontë sisters and Mary Ann Evans (who published under the male pseudonym George Eliot so her work might be taken more seriously), and so many more women like them.

They all experienced pushback from people like poor baby Nat, who feared their success. But there was one thing, one impenetrable buffer, that kept their work in bookstores despite scandal and scorn:

Readers.

The Power You Wield

It was readers that kept female- and minority-written works on shelves.

Readers who continued to spend money on their writing. Readers who recommended books to friends and who bought second and third copies to give as gifts. Readers who snuggled into stolen hours to open themselves up to concepts and characters that were new to them. Readers who passed favorites onto their children and nieces and grandchildren.

Readers. It was always readers.

These readers probably did not view themselves as revolutionaries actively building a more equal and inclusive future, but they were. They turned the gears of capitalism in such a way that the entire publishing industry, in spite of its prejudice against female/minority readers and writers, could not afford to ignore them.

This was true then, and it’s still true today.

Even in an era dominated by algorithms, AI, and automation, readers still have an extraordinary power to shape the literary landscape. Every purchase, every review, every recommendation (in a review on Goodreads, posted on social media, shared in a book club) can amplify voices that might otherwise be drowned out.

Publishing may be dictated by profit margins and marketing budgets, but readers decide what survives. The books that get talked about, the ones that persist, the ones that shape culture, they exist because people choose to champion them.

And in a time when the stories that challenge, disrupt, and expand our understanding are more necessary than ever, this kind of quiet advocacy is nothing short of radical.

So What Can You Do

Read. Read like it matters, slow and intentional or fast and devouring. Just make sure you give each book the time and attention it deserves.

Seek out underrepresented books and voices that resonate with you, that you genuinely enjoy reading. Read those.

Read books that feel cozy, and also books that expand you, stretch you, scare you. Read fiction and non-fiction. Read banned books.

For every book you read by a big name author, read a book by a no-name author. Then for each book, complete the Emerging Author Advocacy Checklist (this is something I made up, feel free to steal it):

Follow the author on their social media accounts. Like, share, and comment on the stuff they post that resonates with you.

Join the author’s email list, if they have one (trust me, no writer has time to flood your inbox with a bunch of emails; you’ll only hear from them when it matters).

Post about their book on social media and tag them.

Leave a 5-star review along with your comments on Goodreads, Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Target, WalMart…anywhere you can buy their book, just copy and paste same review across all sites.

Gift the book to another reader friend and, if possible, buy directly from the author’s website.

If the author releases new writing that interests you, place a pre-order, join their launch teams, street teams, or ARC programs. Most of these things cost nothing but a small amount of your time. It might feel like busy work, but believe me when I tell you that the resulting impact on writers and their work can be astronomical.

Lake Drive Books is publishing my debut memoir on May 6th, and these are things I know we will be watching closely (pre-orders, reviews, ratings, launch team sign ups…) because they all matter tremendously. They are the weathervanes of the publishing industry, and by their twitches and spins we measure the culture’s movement toward advocacy and protest, evolution and revolution.

But the real storm, the force that changes landscapes, isn’t in the numbers alone. It’s in the readers who pick up a book and feel something shift inside them. Who carry its questions into their conversations, who let its truths unsettle them, who wrestle with what it asks of them. It’s in the quiet but radical act of choosing which stories to lift up, which voices to amplify, which ideas to hold onto in a world that too often tries to erase them.

Because books don’t change the world—readers do.

And every time you read with intention, every time you advocate for a story that challenges, deepens, or expands our collective understanding, you’re not just influencing what gets published. You’re shaping the cultural currents that determine what kind of world we’re writing toward.6

Please give us all the gift of tagging a writer that you love in the comments! They don’t have to have a completed book to qualify, but feel free to add a link to their book if they’ve got one.

ICYMI

The Revolutionary Act of Writing

Since signing with my publisher last August, I’ve been busy loading fuel into my debut memoir, and we’re downright hurtling towards its release date…which is (🥁🥁🥁):

This is still happening today. I write about it in my memoir coming May 6, 2025.

Galileo, Copernicus, Protestant Reformers like Martin Luther, and many other great minds were placed on the Index Librorum Prohibitorum (Index of Forbidden Books), established in 1559 by the Catholic Church.

I’ve written about this abhorrent book before and how it was used alongside scripture to fuel the witch hunts: a human holocaust that spanned hundreds of years across multiple continents and targeted predominantly women (including one of my great-grandmothers).

Even though he changed the spelling of his name to distance himself from the scandal of the Salem Witch Trials, we will not forget that Baby Nat directly profited from the theft of property belonging to the victims of the witch hunts thanks to the involvement of his great-great-grandfather, John Hathorne, one of the primary hanging judges.

We don’t know if Anne wanted this or not, whether John genuinely believed in her skills, or whether he profited from her sales.

And, if you’re a woman or a minority, you’re making generations of religious fundy boys angry. Which is something to celebrate. 🙃

Ahhhhhhhh *pounds desk* yes yes yes!!!!

I'm both lucky and biased because some of my favorite boundary-pushing writers are also my clients: Ngina Otiende, Trey Ferguson, *you*... I helped with a beautiful and ground-breaking book of poetry titled Shattered and Gathered, by Johanna Hattendorf, last year. Honestly, I know she's a celebrity and a bestseller, but Beth Moore's memoir deserves every bit of the hype. Lore Ferguson Wilbert is really good, and KJ Ramsey. And my friend Sylvia Mercedes is doing powerful boundary-pushing healing work with her fiction.

Excellent, excellent piece! I was up and cheering by the end of it!